Dazzle camouflage sits at the intersection of warfare, art, and perception. It traded concealment for cognitive interference—an information tactic that corrupts the observer’s perception–estimation–action loop. Rather than hiding the object, it attacked the model in the adversary’s head: course, speed, heading, intent.

This piece takes a disciplined look at that shift. It traces origins and wartime deployments, compares WWI and WWII approaches, and examines effectiveness, maintenance, and the style’s cultural afterlife. This is about extracting principles: how mimicry and misdirection operate under technological constraints, and what they reveal about design’s core work—shaping signals, managing ambiguity, and engineering expectations.

This article’s main role is to lay the groundwork for a subsequent analysis of design, information, and culture—and of how camouflage, through mimicry or dazzle, shapes how people read and understand reality.

updated: November 11, 2025

Disclaimer

This post was not generated by AI.

Artificial intelligence was used selectively during the research phase, primarily for exploratory tasks, and sparingly during the writing phase to review and refine English fluency.

When used in this post, AI is explicitely marked.

All data from publicly available sources.

All opinions expressed in this article are solely my own and do not represent the views of any current or former employer.

Content Structure

- i. Origins

- ii. World War I

- iii. World War II

- iv. WWI / WWII comparison

- iv.i Purpose & Effectiveness

- iv.ii Design Approach

- iv.iii Technological & Tactical Shifts

- iv.iv Military Adoption

- iv.v Theater-Specific Adaptations

- iv.vi Key Elements

- iv.vii Effectiveness Longevity

- v. Modern Times & Critique

- v.i Arguments for limited effectiveness

- v.ii Arguments for its utility

- vi. Dazzle Camouflage Paint Longevity

- vi.ii Maintenance Cycles

- vi.iii Environmental Wear

- vi.iv Operational Relevance

- vi.v Historical vs. Modern Context

- vi.vi Conclusion

- vii. Design & Cultural Influence

- Notes & References

dazzle

/ˈdaz(ə)l/

intransitive verb

1. to lose clear vision, especially from looking at bright light

2. to shine brilliantly

3. to arouse admiration by an impressive display

transitive verb

1. to overpower with light

2. to impress deeply, overpower, or confound with brilliance

The concept of dazzle camouflage (also known as Razzle Dazzle in the US) emerged from competing visions of how to protect naval vessels.

i. Origins

On one side was John Graham Kerr (18 September 1869 – 21 April 1957), focused on invisibility; with a background in the natural sciences, Kerr’s view of camouflage was heavily influenced by the natural world. Kerr’s camouflage framework was based on disruptive colouration and countershading^2, as described and formalised by the American painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer (12 August 1849 – 29 May 1921).

The approach pursued by Thayer and Kerr sought invisibility through mimicry: even disruptive colouration was intended not to detach the subject from its context, but to make it melt into it.

mimicry

/ˈmɪm.ɪ.kri/

noun

a superficial resemblance of one organism to another or to natural objects among which it lives that secures it a selective advantage (such as protection from predation).

On the other side we have Norman Wilkinson (24 November 1878 – 30 May 1971), a British marine artist and naval officer, who reimagined camouflage as a tool for deception.

"Since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer–to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading."

– Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve lieutenant-commander Norman Wilkinson, quoted in Dazzle Ships: World War I and the Art of Confusion (Chris Barton, Millbrook Press, 2017)

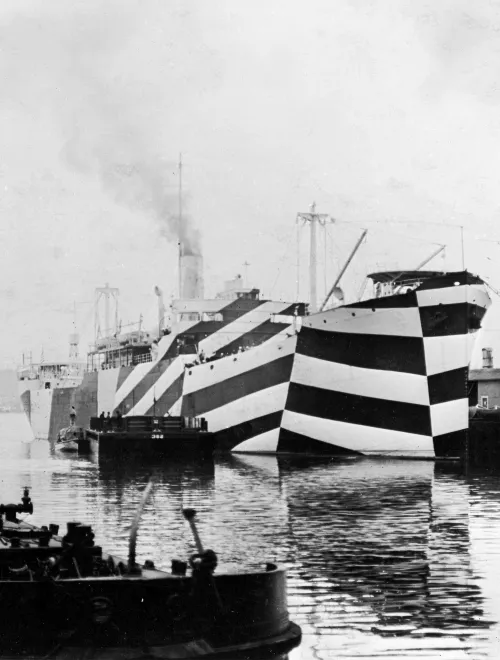

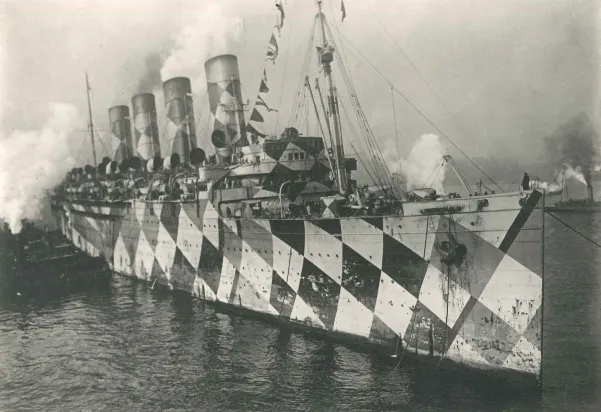

In 1917, Wilkinson introduced dazzle patterns characterized by stark geometric contrasts—black, white, and gray shapes intersecting at sharp angles.

Wilkinson aimed to create optical illusions that misled observers about a ship’s course. For example, false bow waves and contradictory funnel markings could make a vessel appear to be turning or moving at inconsistent speeds.

deception

/dɪˈsepʃən/

noun

the act of causing someone to accept as true or valid what is false or invalid

ii. World War I

By 1918, over 4,000 British merchant ships and 400 naval vessels had adopted some type of dazzle camouflage designs, each pattern unique to prevent class recognition.

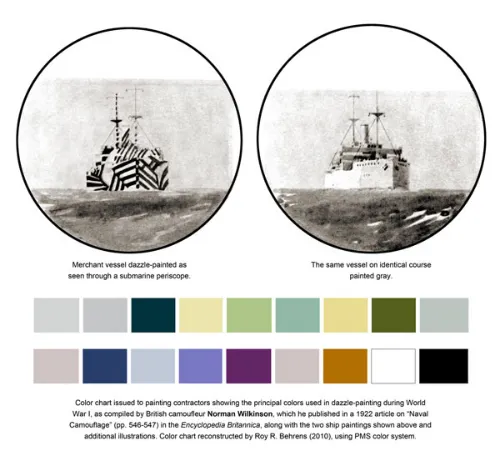

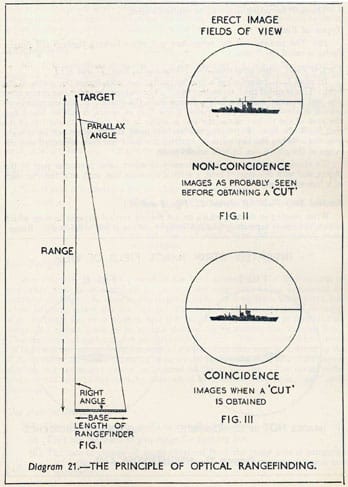

Dazzle’s effectiveness hinged on its ability to interfere with coincidence rangefinders, critical tools for targeting naval artillery. These devices required operators to align split images of a target; dazzle patterns disrupted this process by introducing visual noise. Vertical stripes on masts, for instance, made it difficult to discern the ship’s true orientation, while curved hull markings simulated false motion.Principle of Coincidence Rangefinder

The coincidence rangefinder obtains the range of an object by measuring the angle subtended by the rangefinder at the object. The size of the angle depends on the length of the rangefinder and the range of the object. As the former remains constant, any angle will have a definite corresponding range; therefore, although an angle is measured, the scale on which the answer is shown can be marked with the range.

The length of the rangefinder is small compared with the range of an object, and the angles involved are, therefore, very small. At long ranges the angles are extremely small, and at short ranges the angles are relatively large. Ranges and angles do not change at the same rate. For instance, a change in angle of, say, one minute will have a much smaller effect on range at short ranges, than at long ranges. This has the following results:

i. The spaces between graduations for a given number of yards on the range scale decrease as the range increases.

ii. An error in measuring the angle has a greater effect at longer ranges.

iii. A long rangefinder is more accurate than a short one, because a long base length increases the size of the angles to be measured.

-- The Gunnery Pocket Book, 1945

ii. World War I

By 1918, over 4,000 British merchant ships and 400 naval vessels had adopted some type of dazzle camouflage designs, each pattern unique to prevent class recognition.

Dazzle’s effectiveness hinged on its ability to interfere with coincidence rangefinders, critical tools for targeting naval artillery. These devices required operators to align split images of a target; dazzle patterns disrupted this process by introducing visual noise. Vertical stripes on masts, for instance, made it difficult to discern the ship’s true orientation, while curved hull markings simulated false motion.

Principle of Coincidence Rangefinder

The coincidence rangefinder obtains the range of an object by measuring the angle subtended by the rangefinder at the object. The size of the angle depends on the length of the rangefinder and the range of the object. As the former remains constant, any angle will have a definite corresponding range; therefore, although an angle is measured, the scale on which the answer is shown can be marked with the range.

The length of the rangefinder is small compared with the range of an object, and the angles involved are, therefore, very small. At long ranges the angles are extremely small, and at short ranges the angles are relatively large. Ranges and angles do not change at the same rate. For instance, a change in angle of, say, one minute will have a much smaller effect on range at short ranges, than at long ranges. This has the following results:

i. The spaces between graduations for a given number of yards on the range scale decrease as the range increases.

ii. An error in measuring the angle has a greater effect at longer ranges.

iii. A long rangefinder is more accurate than a short one, because a long base length increases the size of the angles to be measured.

-- The Gunnery Pocket Book, 1945

“[W]hen capable, feign incapacity; when active, inactivity. When near, make it appear that you are far; when far away, that you are near. Offer an enemy a bait to lure him; feign disorder and strike him. . . . When he concentrates, prepare against him; where he is strong, avoid him. . . . Pretend inferiority and encourage his arrogance. . . . Keep him under a strain and wear him down.” – Sun Tzu, The Art of War

iii. World War II

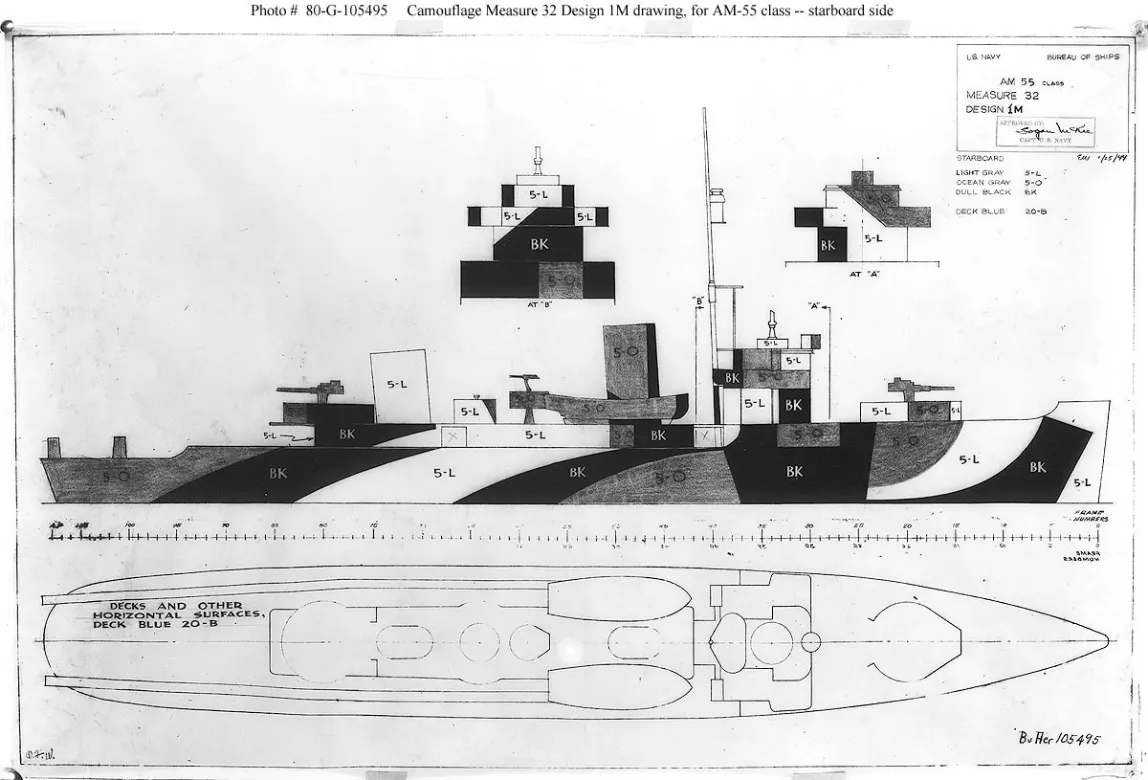

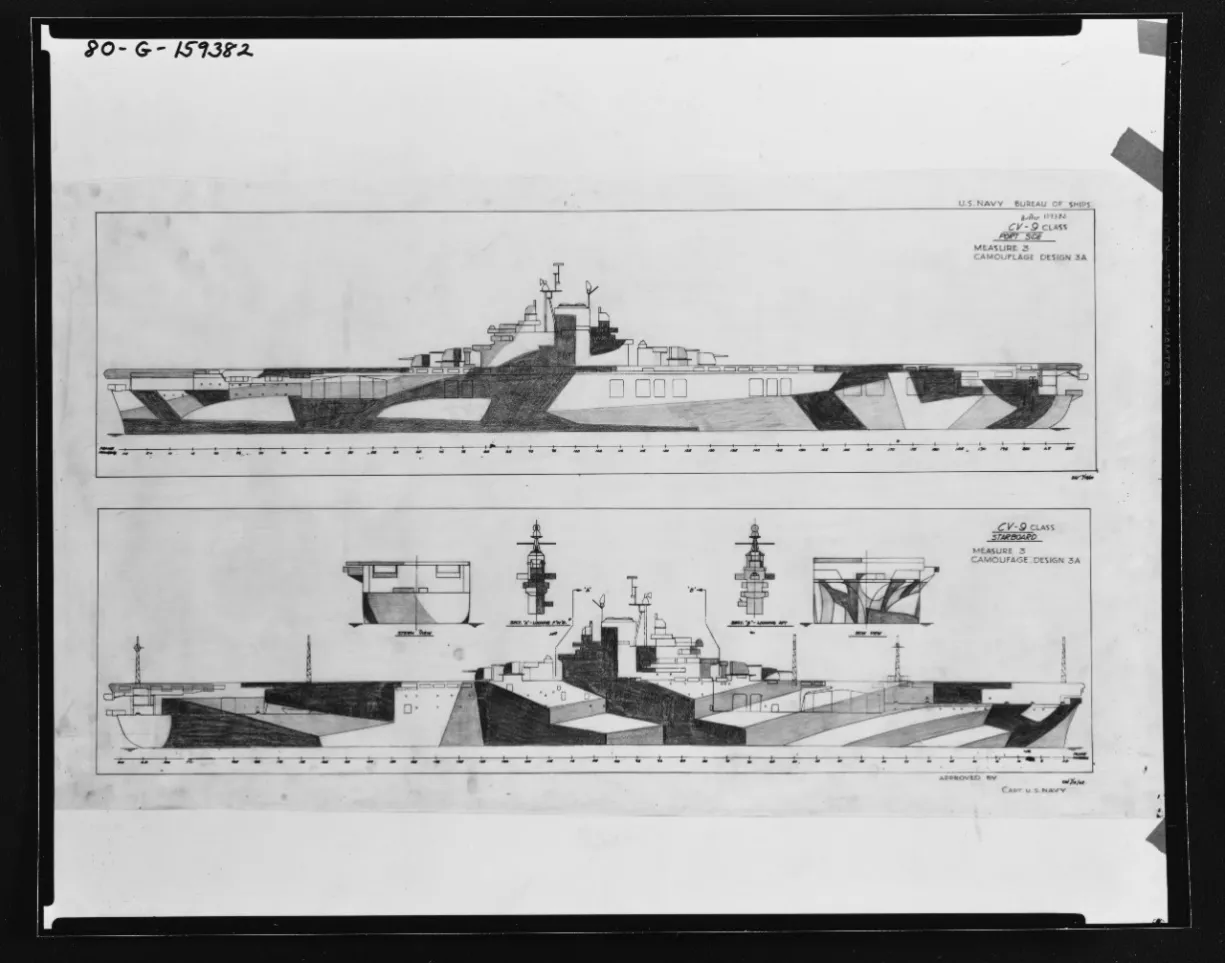

The U.S. Navy standardized “Measure” schemes, ranging from false bow waves to intricate geometric designs, though these were phased out by 1945 in favor of uniform paints to counter kamikaze threats.

The German Navy (Kriegsmarine) initially adopted dazzle camouflage for their ships starting with the invasion of Norway in 1940. The battleship Bismarck and cruiser Prinz Eugen were painted with monochrome patterns to disguise their size, featuring black stripes on the hull and superstructure.

Other ships like Scharnhorst and Admiral Scheer had unique patterns to obscure their identities. However, after 1941, the Navy reverted to using uniform grey tones, leaving the reasons for this shift open to speculation—possibly due to skepticism about dazzle's effectiveness or other strategic considerations.

Examples of Japanese ships using dazzle camouflage are quite rare, the Saga Maru, a converted cargo-liner is one of those few examples.

iv. WWI / WWII comparison

The dazzle camouflage used in World War I and World War II differed significantly in purpose, design, and technological context, reflecting advancements in warfare and naval strategy.

iv.i Purpose and Effectiveness

WWI / Designed to confuse submarine periscope operators by distorting a ship’s speed, direction, and size through high-contrast geometric patterns.

The goal was to reduce torpedo accuracy.

WWII / With radar, rangefinders, and aircraft reducing dazzle’s tactical value, its role shifted. While still used to disrupt visual targeting (especially in coastal/littoral zones), it became more symbolic—boosting crew morale and creating a distinct squadron identity.

iv.ii Design Approach

WWI / Art-driven: patterns were unique to each ship, created by artists like Norman Wilkinson and inspired by Cubism; Bold colors: black, white, and vibrant hues created jarring contrasts.

WWII / Standardized schemes: The U.S. Navy introduced systematic “Measures” (e.g., 31, 32, 33) with prescribed color palettes (Ocean Gray, Haze Gray); Adaptive patterns: Designs were reused across ship classes (e.g., destroyer patterns applied to battleships); Subdued tones: Colors shifted to grays and blues to blend with sea environments.

iv.iii Technological and Tactical Shifts

WWI /Relied on human visual deception, as U-boats calculated trajectories manually via periscopes.

WWII / Radar and aircraft made dazzle less effective in open waters; Germany adopted dazzle for coastal camouflage, blending ships into Norway’s cliffs; the U.S. emphasized Blue Flight Decks to counter aerial threats.

"Blue Flight Deck Stain was in place on all US carriers pre-December 1941. Ranger entered Norfolk Navy Yard on 12 July 1941 for an overhaul and upgrade of armament and radar equipment as well as a weight reduction program. During this yard period, which lasted until 17 September 1941, Ranger painted up in Measure 12 Graded and her deck was stained with Blue Deck Stain, Norfolk Formula No. L-81-3m."

Adoption of Blue Flight Deck Stain on US Navy carriers – Shipcamouflage.com

iv.iv Military Adoption

WWI / Over 2,300 British ships and 1,256 U.S. ships painted, with merchant vessels prioritized.

WWII / Broader application: Used on aircraft carriers (e.g., Essex-class), auxiliaries, and battleships; Psychological role: The Royal Navy’s Western Approaches Schemes and U.S. measures emphasized unit cohesion.

iv.v Theater-Specific Adaptations

Atlantic/European Waters: Focused on low-visibility grays and horizon-blending for surface engagements.

Pacific: Prioritized dark blue and dazzle against aerial threats. Measure 32’s polygons were standardized for classes like Fletcher-class destroyers to obscure identification.

iv.vi Key Elements

| WWI | WWII | |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern Uniqueness | Each ship had a distinct design | Standardized patterns across classes (e.g., Iowa-class battleships) |

| Color Palette | High-contrast black, white, red | Subdued grays, blues, and Deck Blue |

| Primary Threat | U-boats with periscopes | Radar, aircraft, and kamikazes |

iv.vii Technological Limitations

Radar Advancements: By 1945, radar reduced dazzle’s effectiveness, prompting the US Navy Pacific Fleet to switch to non-dazzle schemes against kamikazes.

Submarine Threats: Dazzle remained partially effective; U-boat captains reported misjudging ship courses due to false bow waves and clashing patterns.

v. Modern Times & Critique

There is historical debate over whether dazzle camouflage was effective during World War I. While it was designed to confuse enemy gunners by disrupting a ship's outline and making it harder to estimate range and speed, its practical effectiveness remains unclear.

Modern research has validated aspects of Wilkinson’s approach.

Studies by Nicholas E. Scott-Samuel in 2011 demonstrated that high-contrast patterns could distort speed perception by 7%—enough to cause targeting errors for fast-moving objects.

While less impactful for slow-moving World War I ships, this principle found relevance in contemporary applications, such as confusing missile guidance systems.

A study by researchers from Abertay University (Dundee, Scotland) and Aston University (Birmingham, England) challenges long-held assumptions about the efficacy of dazzle camouflage. Published in Royal Society Open Science (December 2024), the analysis combined historical ship modeling, perceptual psychology, and simulated torpedo attacks to evaluate how visual biases influence camouflage performance.

The team reconstructed the RMS Mauretania, a dazzle-painted troop carrier, in a virtual environment and tested 16 participants’ ability to judge ship direction under varying camouflage designs. While certain textures successfully distorted perceived heading (e.g., making ships appear to “twist” off-course), these effects were frequently counteracted by the “horizon effect,” where observers subconsciously aligned ships’ movements with the horizontal plane. Maritime-experienced participants proved less susceptible to this bias, suggesting trained submarine crews might have partially overcome dazzle’s illusions—a critical caveat to its historical effectiveness.

The study revealed that dazzle’s utility depended on context: when perceptual distortions amplified horizon bias, ships gained protection, but in scenarios where camouflage reduced this bias, attackers gained targeting advantages. Notably, the Ukrainian Navy’s 2024 adoption of dazzle patterns for drone defense—cited by researchers—highlights its enduring potential in human-visual targeting systems, though AI-driven weapons may eventually negate these benefits.

“Human vision won’t have significantly changed since 1918, so if it was fooled by dazzle then, it will be fooled now. The key question is whether targeting involves human perception and a prediction of future location.

If a weapon (torpedo, missile or drone) is visually aimed by a human, then a misperception of direction could still be key.

If the drone uses AI trained on natural scenes, then it could still be fooled by forced-perspective cues.”

– P. George Lovell, Abertay University, Division of Psychology & Forensic Sciences

Today the Royal Swedish Navy (Svenska Marinen), as well as the Finnish Navy (Merivoimat) use a variation of the Splinter camouflage pattern that is reminiscent of the Dazzle camouflage.

v.i Arguments for limited effectiveness

Technological Limitations: During WWI Germans used advanced stereoscopic rangefinders, which could calculate distance more accurately than older coincidence rangefinders. This reduced the impact of dazzle patterns, as they were not as disruptive as intended.

Naval Doctrine Shifts: By the end of the war, heavily armed convoys and escort ships became more critical in combating submarine threats, overshadowing the role of camouflage.

"A type of ship camouflage, entirely separate and distinct from concealment painting, was developed by an American painter, Abbott Thayer, before the first World War and carried to a fine art by Everett Warner, one of America's foremost painters, during World War II. Although applied to a few ships of the U. S. Merchant Marine in 1918, it was little used by the U. S. Navy before 1943.

The purpose of this system was not to conceal, but to deceive observers as to the course of the ship by painting a false perspective pattern on its sides and superstructure. It was believed that in many situations, particularly against enemy submarines, the advantage gained through falsification of the ship's course would more than offset any increase in the range to which it could be detected visually.

The chief objections to deception painting are:

(a) Most of the course deception designs completely disregard, and lessen the possibility for, concealment.

(b) The false impression of a ship's course occurs only from visual observation and only at relatively short ranges after the true course has been well plotted from radar or sonar. Also, within short ranges a spread of torpedoes more than offsets any last minute false estimate of course. Hence, the objective of making the ships harder to hit was not achieved.

(c) The high contrasts in the "Dazzle Pattern" ships make them more conspicuous close aboard and hence attractive targets at close range. It was claimed that some of the ships hit had been singled out by Kamakazi bombers because of their conspicuity.

It is ironical that the majority of criticism from the Fleet which cited increased visibility as one of the chief objections to course deception painting, objected most frequently to the very feature--namely, the light shade of paint used--which probably reduced the ship's visibility as often as it increased it.

Also, in justice to the course deception system, it should be noted that the system in one form or another had a limited success as a ship type deception device. This argument was at one time advanced by some of the British advocates. However, the British adopted a policy (1946) which calls for reduction of visibility first, course and type deception second."

-- Ship Concealment Camouflage Instructions - United States Navy - Navships 250-374, January 1953

The above US Navy manual incorrectly assigns to Razzle Dazzle invention to American painter Abbott Thayer.

v.ii Arguments for its utility

Intended Purpose: Dazzle patterns were primarily meant to disrupt targeting rather than provide full invisibility. While not foolproof, they may have caused enough confusion to delay enemy aim or reduce accuracy.

Psychological Impact: The bold, colorful designs boosted Allied morale and made sailors feel more confident in their ships' ability to avoid detection.

While dazzle camouflage was innovative and visually striking, its actual military effectiveness is often debated. Its psychological impact on Allied crews may have been more significant than its tactical value.

vi. Dazzle Camouflage Paint Longevity

The longevity of a dazzle camouflage paint scheme on a ship depends on operational needs, environmental conditions, and maintenance practices.

vi.i Maintenance Cycles

Modern naval ships typically undergo repainting during routine maintenance periods, which occur every 12–24 months depending on operational demands. For example, HMS Tamar’s dazzle scheme was applied during a scheduled maintenance period at Falmouth, using 200 liters of paint across her hull.

vi. ii Environmental Wear

Saltwater, UV exposure, and weathering degrade paint over time. Historical dazzle schemes in World Wars I and II required frequent touch-ups, especially in harsh marine environments.

vi. iii Operational Relevance

Dazzle’s lifespan often aligned with wartime necessity.

Post-WWII, most navies abandoned it due to radar advancements, but modern applications (e.g., HMS Tamar) prioritize identity and heritage over tactical utility, meaning the paint may last until the next rebranding or refit.

vi.iv Historical vs. Modern Context

| WWI/WWII | Modern | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | Repainted as needed during wartime | Maintained until next major overhaul |

| Purpose | Tactical deception | Squadron identity/heritage |

| Retirement | Phased out post-war (1945) | Likely retained unless rebranded |

vi.v Conclusion

Dazzle schemes last 1–3 years under typical conditions, aligning with maintenance schedules. While historical patterns faded with technological obsolescence, modern uses prioritize symbolic value, extending their lifespan as long as the navy deems them relevant.

vii. Design & Cultural Influence

Dazzle’s influence extended beyond warfare into civilian domains.

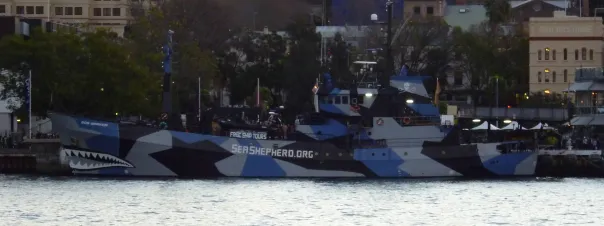

Organizations such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society have repurposed dazzle for symbolic recognition, adorning ships with bold patterns to assert identity rather than concealment.

The Guilty Yacht is a 35-meter-long vessel designed by artist Jeff Koons, commissioned by entrepreneur and contemporary art collector Dakis Joannou, with design input from Italian designer Ivana Porfiri.

The yacht boasts a sleek, trimmed bow and spans across three decks. The geometric designs (yellow-colored rhombuses, pink triangles, and blue polygons) are clearly inspired by WW1 dazzle camouflage as used by the British Navy.

Automotive manufacturers adopted similar patterns to obscure prototype designs during testing—a practice exemplified by Red Bull Racing’s 2015 RB11 Formula 1 car, which used dazzle to thwart aerodynamic analysis by competitors.

For many years, the automotive industry has employed specialized vehicle wraps to mask the contours and proportions of new models during road and track testing—a practice that remains common today. This technique routinely appears in “spy shots” published on car enthusiast blogs, with recent examples showcasing the next-generation Toyota C-HR’s striking design as well as various prototypes highlighted in features like “Car Spy Photos – The Future Automotive Industry Right Here, Right Now.”, and "Secret Cars Kept Under Wraps, in Public" on the New York Times.

Similarly, Manchester United’s 2020–21 football kit incorporated dazzle-inspired designs, merging historical military aesthetics with modern sports branding.

In the digital age, artist Adam Harvey reimagined dazzle as computer vision dazzle, using geometric patterns to thwart facial recognition algorithms.

By creating “anti-faces” through strategic occlusion and color distortion, Harvey’s designs aim to disrupt AI systems like DeepFace, highlighting ongoing relevance in privacy protection.

![Dan Williams has a go at some CV Dazzle 'camoflage [sic] from computer vision' techniques to resist facial recognition software at dConstruct (September 2013) - Rain Rabbit](https://pianabianco.com/inout/content/images/2025/11/danw.webp)

CV Dazzle, conceived by artist Adam Harvey for his 2010 master’s thesis at the New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, uses bold patterns to thwart computer vision systems without obscuring the wearer from human observers—making it the first documented camouflage approach aimed specifically at breaking a computer vision algorithm.

This proof-of-concept research project demonstrated how bold, strategically placed patterns could thwart the widely-used (now deprecated) Viola-Jones (Paul Viola, Michael Jones paper: Rapid Object Detection using a Boosted Cascade of Simple Features) face detection algorithm by disrupting the system’s expected facial feature outlines (haarcascades).

In this sense, CV Dazzle is consistent with the original goal of dazzle camouflage as intended by Wilkinson, that is a mean to deceive and disrupt observers' understanding of the target, by tricking the tools used, as opposed to hide or make the target "invisible".

Is the shirt wore by MI5 Deputy Director-General and Head of Operations Diana Taverner in the final episode of Slow Horses 3rd season a countermeasure to CCTV tracking?

Dazzle camouflage patterns have been explored quite often by fashion designers and fashion brands in general, one of example is this dress wore by Taylor Swift.

✺

Notes & References

Dazzle camouflage on Wikipedia

The Art of Dazzle Camouflage Ships: History and Design

The Rise and Fall of Dazzle Camouflage

The Advent of Naval Dazzle Camouflage

Camouflaged Ships: An Illustrated History

Sam LaGrone / March 1, 2013 12:09 AM - Updated: March 1, 2013 2:22 PM

Boats of the Ukrainian Navy received “dazzling camouflage

Royal Swedish Navy - Svenska Marinen K31 HSwMS Visby

Bismark Line Drawings and Paint Schemes

✺✺✺